For the first time in my life, nobody invited me to a traditional family Thanksgiving dinner. My parents went to Los Angeles to spend it with my brothers’ families, which has been their habit ever since the adorable nieces were born. Paul and I thought that surely, somebody in Paul’s family would host — because they always have before. We’ve been dating since 1988, and until now, every year has brought us to some branch of his family for the annual ritual sacrifice with pie.

So I woke up this morning with no idea at all what to do with myself. I had morning insomnia, which is that thing where you wake up ridiculously early for no reason? And it pretty much never used to happen to me until I was on the north side of forty, so it makes me grumpy both as an irritating thing to happen, and as a reminder of the inexorable press of mortality.

Then I watched The Fault in Our Stars (rented from Scarecrow) because I just finished the book. I still can’t decide if a gut-wrenching three-hankie movie about the inevitability of death was the best or the worst possible way to deal with my emotional funk. (The Fault in Our Stars is about attractive young people who fall in love and then die of cancer. Happy Thanksgiving!) The scene when doomed Augustus pre-hosts his funeral so that he can attend was so hauntingly like Jay Lake throwing his own wake so he could enjoy the party, even if nothing else in the movie resonated, that bit would have gone through me like a Chumash knife.

After my eyeballs recovered from the weeping, I spent some time looking at Facebook and other social media, but the steady stream of Thanksgiving-related messages started to seem not cheery, but overwhelming and vaguely depressing. Did I have to “like” every “Happy Thanksgiving” post? Did I have to “like” anything? Would people feel neglected if I stopped giving them electronic ego validation? I mean, clicking “like” is just about the easiest thing you could possibly do, and yet it started to feel weirdly burdensome. There was just too much, too much everything. I couldn’t sort it out. I wasn’t feeling thankful. I wasn’t sure what I was feeling.

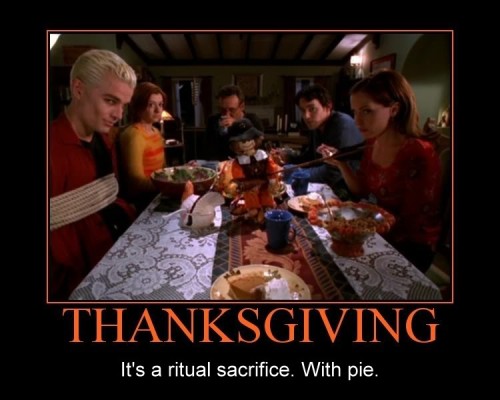

Still at a loss, I engaged in a bona-fide Thanksgiving ritual for me: watching “Pangs,” the Buffy the Vampire Slayer Thanksgiving episode. This year, for obvious reasons, the thing that really resonated was Buffy’s slightly irrational determination to gather around all the family she could manage, and have a proper Thanksgiving feast. In a way, it’s an important marker on the road to adulthood — the first time you have to make a holiday for yourself. It forces you to decide how you feel about it. Do you care if you celebrate or not? Which rituals mean something to you? Maybe it’s a little weird that I could get so late in my life without it ever coming up.

During the BTVS episode after “Pangs,” I fell asleep on the couch. I woke up about forty minutes later, certain deep in my heart that what I really needed was cranberry sauce — the kind you make from fresh whole cranberries, not the canned kind you can slice. (Although it always amused me that my brothers called the canned variety “dog food.”) I grabbed a shopping bag and headed out to the QFC to irritate the clerks working on Thanksgiving.

Once outside, I realized how awful and grumpy and sorry for myself I had been. I’m not at the true center of any tragedy just at the moment, yet still have a sense of overpowering gloom as tragedies accumulate within my radar: friends and family with medical and other worries, the people who keep leaving us, the events in Ferguson. Any sense of thankfulness on my part — it would have seemed almost — selfish, in a way. You know, it’s easy to tell the universe “thanks” when your life is going all right, isn’t it? But what about everyone else? There is suffering out there, real hardcore suffering, and the big tragedy in my life is that nobody else invited me over for dinner. As if I don’t know how to cook.

I determined that I was going to do more than make cranberry sauce. I was going to get all the necessary Thanksgiving items. Potatoes for mashing. Sweet potatoes for cooking in any manner that does not involve marshmallows. Dinner rolls. Eggnog. I was even going to get a TURKEY, damn it! I was going to get the smallest turkey they had and I was going to cook it myself! Yes! And if they had a potato ricer, I was going to get that! Yes! A potato ricer!

(Note: I did not see a potato ricer.)

One question at the heart of The Fault in Our Stars is this: are we more correct to be resentful over the inevitability of loss and pain, or grateful for having ever been here at all? Gratitude — thankfulness — is certainly a more pleasant emotion, but it can seem like a lie. We get these perfect little moments of grace, where everything in the universe feels right, and then — that’s it. That’s what you get. Whatever you love, it will be gone someday, and so will you. Does it matter that you loved, or were loved? If it did matter, how would you know?

The oppressive fog of my malaise lifted a bit as I walked through the park near our place — it’s a sad little park, strangely designed, with too much gravel and not enough trees. But it’s still a park. I passed a line of people in dark coats standing outside the Target building and thought, “did they open a soup kitchen for Thanksgiving?” Then I realized they must be people waiting for “Black Friday” deals, which brought the gloom back. What could you possibly get at Target — or Best Buy — or anywhere — that would make it worth standing in line like that? On a holiday? It did make whatever I was going to do with the rest of my day seem better. I might be wasting it on Buffy reruns and ennui, but it could be worse.

QFC was neither empty nor terribly busy, and the employees did not act particularly irritated to be there. They seemed pretty cheerful, actually. I still felt guilty for implicitly being the reason they had to work on a holiday. But maybe, given that they were there anyway, it was better not to be bored. I bought a turkey breast portion, which was half the size of the whole turkeys. I bought all the other things on my mental list, and walked home, frozen turkey carcass swinging in one hand, shopping bag over the other shoulder.

The Internet suggested that I could roast a turkey that was still frozen, so I did that. First, I coated the outside in dry rub from my Memphis Blues Cookbook. I had been so impressed by the results of that same dry rub on chicken grilled over fire, I was convinced that it was a magical substance that would render any poultry thus anointed indescribably delicious.

Cranberry sauce was super easy. Water, sugar, cranberries, and boiling.

Mashed potatoes was also easy, because I bought Yukon Gold potatoes, and it’s hard to go wrong with those. I used a hand masher. I don’t think a ricer would have given me better results.

The turkey roasted for 3 hours at 400 degrees. Most online advice gives 350 as the ideal temperature, but after running it at that temperature for a while it didn’t feel right somehow, so I kicked it up a notch. It was frozen, I was impatient, and I felt like the dry rub would help protect it. It came out very close to exactly how I wanted.

If I do this again, I will probably get a whole free range turkey from the co-op. And a meat thermometer and a bigger pan, and maybe one of those basters with the yellow squeeze bulb purely in honor of my grandfather, who used one of those to fuss over the turkey all morning every Thanksgiving of my childhood.

My grandfather was the first person in my life who I lost to cancer. I was thirteen. I wish I could say that he taught me how to cook a proper turkey, but he didn’t. We kids were never expected to help with dinner except in extremely minor ways: prepping the brown-n-serve rolls; opening a jar of olives; putting out napkins. I can’t tell you any of his secrets for perfect turkey. All I really remember is that baster with the yellow squeeze bulb, and his palpable joy as he tended the roasting bird.

For no reason that makes sense, cooking the official ceremonial foods actually did make me feel better about things. And now I have the most important part of any Thanksgiving feast: leftovers.