Images of a sad and wasted childhood

I was skeptical — but a little worried too. The people who believed in all that stuff sounded so sure of themselves. Maybe they knew something I didn’t? How could you know for sure? But as the levels of nutty-ism in the church rose higher, and I got older, eventually I rejected the whole thing. My faith shattered when I was about fifteen years old.3

I spent a long time afterward trying to figure it out. What was wrong with people that they could believe such outrageously absurd things based on no evidence at all? Were they lying? Crazy? Deeply stupid? I also had a lot of anger to process. I felt betrayed, baptized in what came to seem like a bait-and-switch: get dunked for love-your-neighbor-hippie Jesus and stay for right-wing-gay-hating-tough-guy Jesus!

This kind of thing would scare anybody.

Also, there is the matter of Hell. If you weren’t raised in a Hell-believing religion, it’s probably hard to comprehend how real and deep and horrifying the fear of it can be. I mean — it’s a made-up thing, right? Nobody’s ever seen it. But in the mind of a kid, “Hell” is like “France” or “protons” — sure, you’ve never seen it yourself, but you grow up in a culture that assumes it’s real, so you do, too.

When I was young enough, the fact that I couldn’t figure out how to prove Hell existed just made it scarier — what did everybody else know that I didn’t? Was my own damnation the reason I couldn’t figure it out? But then I reached snotty teenagerhood, and realized there was no more reason to believe in evangelical Hell than there is to believe in any other horrible thing your imagination can conceive. 4

The instant I stopped fearing Hell, I became furious that I had ever been made to fear it. But I also remained fascinated and a bit haunted by memories of that fear. I’ll probably always be a sucker for horror and dark fantasy that treats Hell as a literal place. Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, for example.

I was a huge fan of Sandman when Good Omens came out.5 I think I had vaguely heard of Terry Pratchett, and thought of him as being in a category with, say, Robert Lynn Asprin — a writer of light, pun-filled fantasy romps.6 But Good Omens turned out to be another bait-and-switch, this one entirely delightful: come for the Gaiman and stay for the Pratchett.

Good Omens came out in 1990, and I read it that year or the next.7 I loved it — it was funny and inventive and deeply humanistic. But more than that, it gave me a new perspective to use to process my relationship with my broken childhood faith. It helped me DEAL, and I don’t know of any higher or better accomplishment for a work of art.

If you don’t want any spoilers — go and read Good Omens RIGHT NOW.

Finished? Then come back and read the rest of this essay.

Good Omens is about the end of the world as predicted by the American evangelicals of my youth, interpreted through the minds of two agnostic-to-atheist English fantasy writers. It takes evangelical end-of-the-world scenarios more or less literally, without taking them seriously.

My childhood fears? Mocked.

My adolescent anger? Validated.

But also, turned into humor. Laughter — no matter how cynical — is always better for the soul than seething stored-up resentment. I finally understood that nobody actually meant to be lying to me about Hell, or demons, or the end of the world, or any of it.8 Everyone, religious or not, has a tendency to believe in things that aren’t objectively real, for reasons that don’t make sense, and then invent a story to explain why, that doesn’t really explain anything.

That’s just human nature. And Good Omens is very much an exploration of human nature, in all its flawed, frustrating glory. Human nature is presumed not to be good, or evil, but both — sometimes alternately, sometimes all at once, sometimes appearing to be one, but really being the other. It’s complicated. And, good or bad, human nature is hilarious, because people are bizarre.

Given that neither author is actually an ex evangelical, it’s surprising to me how thoroughly they manage to skewer what I perceive as specifically evangelical tropes. For example — “Heaven has no taste,” meaning, no good music, movies, or sushi restaurants. Historically, Christians have produced things like cathedrals and Bach. But, by the 80s, having no taste seemed like one of the defining characteristics of evangelical culture, and I sometimes felt like I was the only one who noticed. I mean — “Christian Rock” was a thing, okay?9

Books are another example. One of the odd things about evangelicals is the way they venerate the Bible-as-book — worshiping or fetishizing physical Bibles as precious sacred objects unto themselves. They always have multiple editions and multiple copies. at least one encased in a leather slip cover with a dove on the front so that it won’t get damaged as you take it to and from church every week, which you have to do even though the church also has Bibles in the rack in the pew in front of you so you could just use those if you wanted.

But all this book worship is done without any consciousness of the Bible as a historical document, written, translated, printed, and sold by actual human beings at a particular point in time. Because “God wrote it.” I mean, I doubt even the most fuzzy-headed evangelical would claim literally that God went ZAP and a King James translation, New Testament only, bound in white and gold with the actual words of Jesus printed in red, magically appeared in your hands. But they do sorta act like they believe that. Evangelical culture works hard to remove the sense of human agency at work in Bibles and Biblical interpretations.

So, I found it particularly hilarious that Aziraphale — angel and dealer in rare books — collects Infamous Bibles, early print editions nicknamed for errors in typesetting, such as the Wicked Bible with a crucial “not” omitted that instructs the faithful, “thou shalt commit Adultery.” I couldn’t help but imagine a particularly literal-minded “fundamentalist” Protestant getting their hands on the Wicked Bible and forming a spouse-swapping sect.

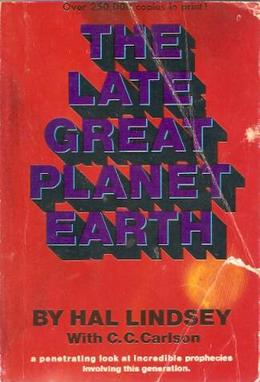

The book most central to the plot, of course, is the one on the subtitle: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, the worst-selling book of prophecy ever, primarily because it was the only one to be completely accurate. So, her book makes a satisfying thematic counterpoint to works like The Late, Great Planet Earth. (Although Good Omens tends to reference only more classical prophetic works, such as Nostradamus and, of course, Revelation itself.)

Good Omens poses the question — even if you had a completely accurate book of prophecy, what good would it do you? For all the generations since Agnes was burned as a witch, her descendants have devoted themselves to attempting to interpret the book — which, while one hundred percent accurate, is far from straightforward, especially once you take into account how the mind of a (highly intelligent) 17th century woman would filter the technology and culture of the 20th century. So, while they have certainly taken some advantage of the foreknowledge it offers, more often than not they find themselves puzzling and puzzling and puzzling over the meaning of something that then seems perfectly obvious after it happens.

Even though Agnes herself is a heroic figure in the book, and one of her descendants (Anathema Device) does use her predictions to help thwart the Apocalypse, overall the book seems to be arguing for the relative uselessness of prophecy. You can spend all your time obsessing over what it really means, but most of the time, it won’t help you anyway.

This exposed, to me, the central theological problem with the evangelical end times obsession: since the doomsday cult evangelicals weren’t actually interested in trying to prevent the Apocalypse, their obsession with it made no difference at all. There was simply no action to be taken that was any different from whatever Christians are supposed to be doing anyway.10

Two of the main viewpoint characters of the book, the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley, are supposed enemies who have become friends, a demonstration of the idea that reasonable people of all religions have more in common with each other than with the more extreme factions within their own “team.”

They’d come up with some stomach-churning idea that no demon could have though of in a thousand years, some dark and mindless unpleasantness that only a fully-functioning human brain could conceive, then shout “The Devil Made Me Do It” and get the sympathy of the court when the whole point was that the Devil hardly ever made anyone do anything. He didn’t have to. That was what some humans found hard to understand. Hell wasn’t a major reservoir of evil, any more than Heaven, in Crowley’s opinion, was a fountain of goodness: they were just sides in the great cosmic chess game. Where you found the real McCoy, the real grace and the real heart-stopping evil, was right inside the human mind.

— Crowley musing in Good Omens

These kinds of observations helped me put my evangelical upbringing in perspective. I realized that I had been brought up to be on the “good” team, by people who (like Aziraphale) were also genuinely good. But there was nothing about the mere fact of being on that particular team that ensured goodness, and nothing about leaving the team that ensured badness. The people still on the team might see it differently — but then again, they would, wouldn’t they?

It was exactly the message I needed, and this was the first place I had ever seen it laid out quite that way.

One of the recurring themes of Good Omens is the difference between the grand plan — the end of the world according to the general evangelical blueprint of the 70s and 80s — and the ineffable plan — the part you don’t know and can’t really understand, the truth behind the truth you think you know.

God does not play dice with the universe; He plays an ineffable game of His own devising, which might be compared, from the perspective of any of the other players [i.e. everybody], to being involved in an obscure and complex variant of poker in a pitch-dark room, with blank cards, for infinite stakes, with a Dealer who won’t tell you the rules, and who smiles all the time.11

–Aziraphale musing in Good Omens

The world does not end, in Good Omens, because the Antichrist (Adam) who was created to destroy the world, instead, comes to love it and want to protect it. The Antichrist ends up being Christ after all. Because he chooses to be. Because the world is awesome and beautiful and worthy of love and it would be a bad thing to destroy it.

The side that wants to destroy the world — they’re the villains. The side that wants to save the world — they’re the heroes. That seems pretty obvious, right? So what does it mean when the “good” side starts to be the side that wants to destroy the world?

In Good Omens, the battle lines are eventually drawn as Heaven and Hell — supposed opposites that are really kinda the same, and which both want Armageddon to proceed as planned — vs. Humanity and allies, who want to save the world.

It’s a metaphor, of course. In the the here and now, “Heaven” and “Hell” are both represented by evangelical Protestants obsessed with demonic forces and looking forward to the end times. They seem to believe God loathes his own creation as much as they do. They ache for the world as it is — messy, flawed, weird, complicated, difficult to understand — to be annihilated and replaced with something simple, clean, perfected.

But if the Creator wanted that kind of world, wouldn’t it be that way already?

If you loved God, wouldn’t you love the world AS HE HAD ACTUALLY MADE IT?

What if the Kingdom of Heaven is something we build right now, with every act of grace or kindness? And what if Hell is also something that we build right now, with our cruelty and indifference? What if the significance of God or gods is not whether they exist in a literal sense, but how they exist in our minds?

These themes show up again and again in Pratchett’s writing, but Good Omens is where I saw them first, and also where they pertain most directly to my experience as an evangelical kid. So that book will always be special to me.

I have no particular faith that Heaven is a literal place. But at the same time, I am certain that Mr. Pratchett was escorted there by a perky goth girl wearing an ankh,12 and that it’s lovely, with plenty of cats, and excellent sushi restaurants.

1. It also features heavily in Waking Up Naked in Strange Places.

2. Apparently none of the other people who went to that church were big fans of Shakespeare. Figures.

3. Also the age at which Abby in Waking physically runs away from her cult family. This is not a coincidence.

4. My imagination is capable of conceiving of some very, very horrible things. I don’t know quite how to feel about that.

5. An opinion I shared with pretty much everyone else I knew at the time who read any comics at all, and also some people who didn’t previously read comics. Now that it’s reached classic rock status, it can be kind of hard to fathom how thoroughly Sandman blew up the world of comics, and changed forever what they were about, who read them, what they expected from them, and what the publishing companies put into them.

6. HAHAHAHAHAHA. He is that, of course. But SO MUCH MORE.

7. Thank you forever, Joy! YOU ARE A GODDESS.

8. Except for the ones that were lying. The problem is, you really can’t tell, and it doesn’t always make a difference anyway, because that’s another thing about human nature.

9. Sometimes I’ll be writing an essay about my evangelical upbringing and find myself going on for paragraphs and paragraphs about how much I hate the phenomenon of Christian Rock, and then I always have to cut it, because it always ends up being beside the point. In short, I didn’t like it because it wasn’t the kind of music I wanted to hear. No big. But then I was part of a culture that kept trying to foist it on me as if it were a reasonable substitute for the more demon-infested stuff I actually wanted to listen to. I saw this as deeply insulting not only to me personally, but to the very concept of artistic taste as a real thing that some people had.

10. Of course, opinions differ wildly as to “whatever Christians are supposed to be doing anyway.”

11. Calvinball, I’m thinking.

12. Yes, I know I have Pratchett escorted to the great beyond by Gaiman’s version of Death instead of his own — that just seemed right somehow. Also, I think it’s significant that both of them have highly charming and sympathetic incarnations of Death in their work.