By special request — an essay ranting about Christian Rock!

I first encountered Christian Rock when I was 12 years old, right in the middle of a very chaotic thirteenth year. (Yes, I just now realized that the year you are twelve is your thirteenth year. Oooooooooo! Superstitiousness!)

My thirteenth year went kinda like this: junior high; menstruation; zits; hair turning into some kind of extruded strawlike substance about which nothing could be done and which my fellow seventh graders seemed to find the most hilarious and mockable thing they had ever seen; moving a thousand miles away; a different junior high; living with friends of the family and being subjected to an inconsistent patchwork of rules and expectations from two sets of parents right when my adolescent brain was starting to chafe under the notion of adult authority of any kind; a third junior high; my mother’s father diagnosed with lung cancer.

All that, and I was twelve. So, you know, I didn’t really know how to deal with any of it.

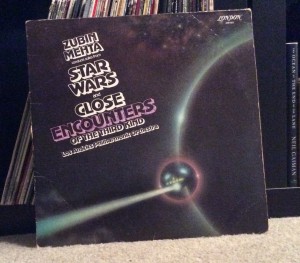

I had picked up on this idea that I was expected to start getting into contemporary pop music, and that this would form the backbone of my generational identity and become a focus for my “youthful rebellion.” But the songs that happened to be popular when I turned twelve were terrible. I had a record player, and my one record was this:

NERD!

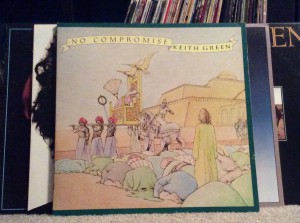

So, when I first encountered Christian Rock, I was open to the concept — I wasn’t already invested in regular contemporary rock. The family we stayed with when we first came up to the northwest had an older boy who didn’t live with them, from a previous marriage I think. (Divorced evangelicals were still a bit of a rarity at that time.) He came by for a visit and brought along a bunch of records. This one intrigued me because of the highly narrative cover art. I thought maybe it was a concept album or something:

You’ll notice this picture was taken in our house. Because Paul still owns it and likes the piano playing.

What is this? I wanted to know.

Oh, it’s Christian Rock, explained the boy. And he launched into an explanation, which I remember as boiling down to “it’s like regular rock, only it won’t send you to Hell.” Then he played me one of the songs:

“Dear John Letter (To the Devil)”

I didn’t really like it.

Musically, it didn’t grab me, but the thing I really disliked was the lyrics — or, rather, the attitude of the lyrics. They’re talking to the devil, but without the intro of the live version I linked above, it sounds like he’s talking to an actual human person who almost “got him in the ways of the world” and if he hadn’t been rescued by Jesus he would now be “cooking, right next to you!” The guy who played it for me sang along vigorously with that line. But until just now I mis-remembered the lyric as “burning right next to you.” Either I subconsciously rewrote it to something I found more interesting, or he sang it wrong.

As I mentioned in the Good Omens essay, I had complex feelings about Hell even before I started to question my faith. I was never able to engage in that evangelical ritual known as “relishing the sure sense that you’re going to heaven and other people aren’t.”

The song was also curiously unspecific about what these dangerous “ways of the world” actually were. Sex? Drugs? Chartered accountancy? It bothered me. I mulled it over a lot. Maybe it was supposed to inspire that — that bothering, that mulling-over — but if so, I think I came to the opposite of the intended conclusion. It formed part of my dawning realization that a lot of evangelical notions of good and bad weren’t really based on the Bible, or on any coherent moral philosophy, but rather were based on a sense of tribalism, on being on the right team. Being rescued by Jesus meant being an evangelical. The “ways of the world” meant not being an evangelical. The end.

First contact with Christian Rock, and I was not won over.

The music that did eventually click with me was oldies, in the form of The Beatles, which led me down a rabbit hole of 60s rock, back up through 70s glam (by which I mean, BOWIE), and emerging into the modern era with punk and new wave.

Meanwhile, back in the strange parallel universe of evangelical pop culture, Christian Rock was becoming a bigger and bigger phenomenon. You know, where your entire youth group goes to a concert, and at the end there’s an altar call? I think I ended up at a couple of those, sorta by default, but I don’t even remember who the bands were. This went hand in hand with rising Satanic Panic about all the diabolical messages hidden within regular rock music. So the intended takeaway was pretty clear: regular rock might send you to Hell, so just to be on the safe side, you should listen to Christian Rock. Only. Ever.

Even if I liked the music, I would have had serious problems with that message. I didn’t believe in the diabolical forces, for one thing. The “evidence” for it was all wacked-out conspiracy-theory stuff, cribbed from the sort of much-photocopied pamphlet that references the Illuminati un-ironically.

I could believe, in theory, that it was possible to encounter the music and like it for the regular reasons that you’d like anything — people sincerely enjoy stuff I don’t like all the time. I could also, in theory, understand that you might want to listen to music that made you feel stronger in your faith, or stay away from music that seemed to weaken it. But all of that is entirely subjective — you have to figure it out for yourself. And part of the phenomenon of Christian Rock seemed to be this sense that maybe you shouldn’t be making that call on your own, that it was dangerous even to think about it too hard, and the demons could get at you that way. (They could get you in the ways of the world.) Instead, you ought to listen to these pre-approved artists who were produced and marketed in a certain way that told you they were “safe” to listen to.

Evangelicals worried that everything carried secrets.

Christian Rock was supposedly a “ministry.” The idealized narrative seemed to be: take your unsaved headbanger friends to this Stryper concert and while they’re rocking out, secretly, they are hearing the message of Jesus! And this was… I dunno, I guess it was supposed to… impress them so much that they would convert on the spot?

Like that ever happened.

Okay, it’s a big world — maybe it happened. Once.

What happened instead, was that evangelicals kept re-saving each other. The music was pushed my way by people who appeared to be trying to convert me to the religion that I was already supposedly a part of.

Evangelicals had this thing — probably still do — where, sure, you’re saved, but you could be more saved. Except not really, because that goes against Christian doctrine. But yes. You could be more saved. Except no. We would never say that one person is more saved than another. That goes directly against what’s in the Bible. But yeah. Still. Kinda they are.

Supposedly your salvation is between you and God/Jesus, with no intermediaries — you have a “personal savior” — but in practice, if your ideas go against what the other people in your church think, they all start to make a point of letting you know that they are very worried about your salvation. They have a burden on their heart for you. They worry about how you’re reading the Bible, what you’re listening to, who you’re talking to, what you’re thinking. Maybe they even stage an intervention, try to steer you back to the “correct” path.

Evangelicals don’t have formal intermediaries or hierarchies. They have PEER PRESSURE.

The culture seemed to buy heavily into the child-as-passive-clay theory (hence, the trend for things like home-schooling) and acted as if there were only two forces at work molding a child: worldly peer pressure that would steer them wrong, and virtuous godly peer pressure that would steer them right. The child’s own self? Eh. Not a factor. So the sales pitch for Christian Rock seemed to assume personal taste wasn’t a thing, and the only reason you’d have to listen or not listen was which peer pressure you were presently caving to.

This made my dislike of Christian Rock a lot more personal than my dislike of any other musical genre.

Which might bring up the question — why didn’t I like any of it, when there were oh, so many different varieties to choose from? Christian Pop, and Christian Folk, and Christian Hard Rock, and Christian… I don’t know, Christian Easy Listening?

But that’s the wrong question. I already mentioned that I frequently disliked mainstream pop hits. With ALL of regular music to choose from, I found what I liked, and nothing from the Christian Rock bubble intersected with that “what I liked” bubble. At the time, I tended to assume (uncharitably) that this was because the hothouse world of Christian Rock allowed artists who weren’t very good to make it fairly big anyway. But it might also have been the sound the producers were going for. Or, it could have been what the songs tended to be about emotionally. I don’t remember songs that tried to convey anguish; loneliness; doubt; rage; fear; despair; loss; darkness. I don’t remember any songs that made me laugh, or made me want to dance.

I don’t remember a sense of mystery or ambiguity or intrigue in the lyrics, or a conscious exploration of the metaphors at work, or anything surprising or weird.

I don’t remember any poetry.

That was the thing that tended to actively put me off — the lyrics, and how they were delivered. Given the way evangelicals fretted over secret meanings in everything, I imagine this was at least partly by design. They were probably comforted by songs that told you a simple story, and told you exactly how you were supposed to feel about it, and exactly what meaning you were supposed to take away from it.

For example, the Amy Grant song “Fat Baby,” which was on an album one of my college roommates used to play. The gist of the song is mocking a guy who goes to church weekly — he’s “saved and that’s all that matters to him” — but his “daily devotions are stuck in the mud.” You know. He’s saved but he’s not saved ENOUGH. Plus, the “fatness” metaphor is really confused, because sometimes being a “fat baby” means he’s selfish and demanding, but he also needs more spiritual “feeding.”

Now, when I listen to gospel, or Johnny Cash doing a religious song, I usually get the feeling that I’m hearing the singer sharing their own passions and conviction. But when I heard Christian Rock it always seemed directed outward, telling the listener what their conviction was supposed to be. It frequently came across as preachy, smug and insular. Are you like Fat Baby guy? Don’t be Fat Baby guy! Make sure your daily devotions are on track, people!

Christian Rock was a perfect example of what Fred “Slacktivist” Clark calls evangelical tribalism It seemed to function as part of the increasing tendency for the faith to be defined by culture rather than conviction — listen to Christian Rock™, watch Christian TV™, read Christian Fiction™, wear Christian Outfits™, have a Christian Hairstyle™.

Which — if that’s the way you wanna do it — I guess that’s your choice. But don’t pretend it’s going to save anybody’s soul.

There’s only one way I ever really liked Amy Grant — as the subject of a Young Fresh Fellows song.