Ground Control to Major Tom

New Year’s Eve, 1980. I was with my immediate family, watching television in a hotel room in Redding California. We were on our way back to King County after spending Christmas with family in southern California. I was thirteen.

Because it was the turning of the decade, the show featured a retrospective on the 1970s. This included a clip of David Bowie performing “Space Oddity.” I don’t remember exactly what he was wearing. It might have been his Ziggy Stardust getup, or the dress with the handprints. What I remember is having two thoughts, right on top of each other.

Thought one: “Oh, I like this song.”

Thought two: “I’ve never seen anybody so cool in my whole life.”

Then the rest of my family started making fun of him for being a weirdo.

My parents seemed disturbed by his not entirely standard gender presentation. My younger brothers were of an age to make fun of anything at all. I doubt it was important to any of them. I doubt they even remember it.

I didn’t speak up, which probably contributed to the illusion that we were all in agreement that David Bowie was a Freak and We McGalliards weren’t entirely down with that.

That is the point at which I became a Bowie fan.

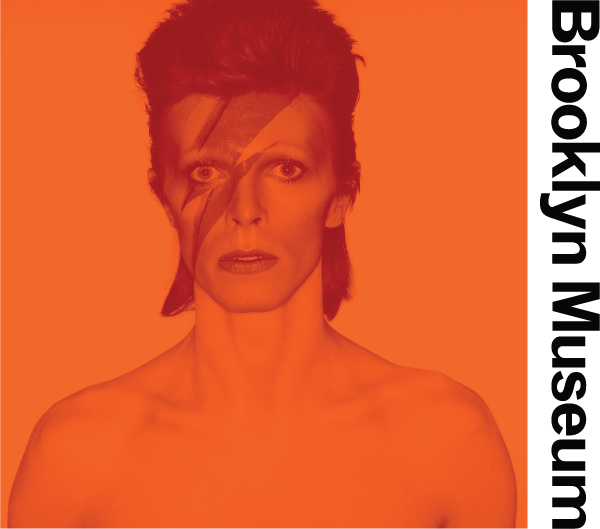

Note: This memory becomes more hilarious now that a clip from the David Bowie Is exhibit has allowed me to pinpoint what the special was (Dick Clark’s Salute To The Seventies) and what his outfit was. It was this:

An olive green jumpsuit. About as un-flashy and heteronormative as Bowie ever got.

Not sure if you’re a boy or a girl

Like a lot of nerdy kids, I grew up feeling like a freak. I never fit comfortably into any of the boxes that seemed to be offered to me to inhabit. That included all the boxes labeled “girl.” Early on, I got the impression that as a girl your options were “girly girl” or “tomboy.” A girly-girl was sort of ruffly and sweet and liked romance and pink things, while a tomboy liked to run around with boys and play sports. But I was a nerd girl. I wasn’t into pink fluffiness OR sports. I was into books and art and science.

This seemed okay at first — a lot of my literary heroines were girls who didn’t fit into the girl boxes of their time or place. I was a feminist, anyway, and therefore ideologically opposed to girl boxes. I could take a simple pride in not fitting in.

But then I hit the age, roughly 10-11, where the girls around me started turning into pre-adolescents.

They read Tiger Beat and Teen Beat. They crushed on boy bands and boyish celebrities and real boys, too. They painted their nails and curled their hair. They wore training bras. They dotted their i’s with little hearts. They doodled boy names on their Peechees. And all these things seemed to arise naturally out of some spontaneous impulse which I sometimes imitated, but never felt or understood.

I could read Tiger Beat — but it just seemed like a boring magazine to me. I was still more interested in Starlog or Mad. I could listen to Shaun Cassidy — but, although I liked him just fine on The Hardy Boys, I didn’t see the appeal of his music (and was also vaguely resentful that Hardy Boys was getting all the attention when there was also a Nancy Drew show on the air, excuse me very much).

There was even a point where, feeling increasingly alienated by the world of girl-dom, I thought about the world of boy-dom. What did boys do? What did boys think? What kinds of boxes did boys get put into? Did I actually belong in one of the boy boxes? But I concluded that I would fit in just as badly as a boy.

Around the age of 13-14, I put forth a deliberate, concentrated effort to try to be a “proper” girl. I tried following the advice and instructions in magazines like Seventeen. I tried listening to the most popular music of the day, fought with my mom to try to get clothes or haircuts that seemed like what the popular girls wore, even tried making friends with popular girls.

I worked hard at this, but had no idea what I was doing. I felt like some Star Trek alien trying to understand this human emotion of kissing. I attempted to generate algorithms for simulating “normal” adolescent girlitude. I ran experiments, including some that in retrospect seem really odd, like deliberately falling asleep listening to top 40 stations, in the hope that sleep learning would somehow instill me with an appreciation of music I mostly kinda hated. I tried doing popular things I didn’t like at all, in the hope that by doing them, I would figure out why other people liked them.

I was faking. I felt like everyone could tell I was faking.

I was just about as miserable as I have ever been.

Then, somewhere around the ages of 15-16, things started to change. I made friends with the kids in the Drama Club. I had gay friends. I saw The Rocky Horror Picture Show for the first time. David Bowie came out with a new album, Let’s Dance, which put him in the spotlight. Artists like Annie Lennox and Boy George made “androgyny” a thing in pop culture. New Wave music was popular, and I liked it.

The world started to make more sense. I realized you didn’t have to put everything in a box. Men could paint their nails or wear lingerie. Women could slick back their hair and wear suits. The things you did could just be the things you chose to do, whatever seemed good to you, totally for your own reasons. Other people might like it, or not, but that was okay.

I didn’t have to fake being a “regular” girl, or fake anything at all. I could just be me. Kind of a freak and a weirdo, but that was okay, because the world was full of freaks and weirdos. Like Bowie. And they were fabulous.

Oh no love, you’re not alone

Back in the 80s, Tower Records used to have this thing — I think it was annual, early in the year — when just about their entire back catalog of vinyl would go on sale. I think the standard price was $6, which seemed cheap even then. On my way back to college for the semester, I bought two Bowie albums. One, Diamond Dogs, was because a friend of mine liked it. The other, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, was because it seemed to be his most highly regarded album.

Prior to that, my Bowie collection consisted of a cassette tape with Let’s Dance on one side and Changes One Bowie on the other. A friend had made it for me. Most of my friends liked David Bowie. He seemed to straddle the line between what hipster New Wave gay kids liked, and what old-school classic rock types liked.

Ziggy Stardust says TO BE PLAYED AT MAXIMUM VOLUME and I did. I was alone in the dorm-slash-apartment, back from winter break earlier than my roommates. When I played the album for the first time I knew “Ziggy Stardust” and “Suffragette City,” of course, but I didn’t know “Five Years,” “Moonage Daydream,” “Lady Stardust,” or “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide.”

To think. There was a time when I had never previously heard “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide.”

If you know that song — and if you don’t, go listen to it right now, okay? I’m waiting. Finished? So now you know all about its world-weary romanticism, its evocative lyrics, its slow build from acoustic guitar ballad to full-on anthem, flirting with cheesiness. Sentiments like “you’re not alone” or “you’re wonderful” can seem smug or facile in the wrong hands. But delivered in Bowie’s raw, impassioned vocals, they come across as a desperate last hope reach for salvation. You’re not alone. You’re wonderful. Give me your hands. Let me talk you off that ledge. Let me take away the gun.

It’s a perfect song to end a perfect album. When the final chord sounded, I played the whole thing again.

And again.

And again.

Somebody knocked on the door, and I was sure it was a neighbor who was going to tell me to turn it down or at least stop playing the same damned album over and over. But instead it was a neighbor who recognized it as an album that had belonged to her older sibling, which she had always loved but never made note of what or who it was. She didn’t want me to turn it down. She wanted me to make a tape of it for her.

Bowie brings people together.

Putting out fire with gasoline

During most of my growing up, I almost never saw new movies. The whole family might go out to see the latest Star Trek or Star Wars or James Bond, and sometimes my high school friends and I went to new movies. But it wasn’t frequent, and it was neither prestigious — you know, the kind of serious drama likely to win an Oscar — nor artistically adventurous, except for my old “cult” friend Rocky Horror. Back in those days before home video really took off, a suburban kid without a car didn’t have a lot of cinematic options.

But I loved movie reviews. I read everything John Hartl wrote for The Seattle Times and followed Siskel and Ebert from Sneak Previews to At the Movies. I actively looked forward to the day when I would be an adult, and able to see any kind of movie I wanted whenever I felt like it. Especially — dark secret, here — horror movies. Especially vampire movies. Especially The Hunger.

You know, because it starred David Bowie.

Early in college, I went to my first science fiction convention — VikingCon, at Western Washington University — and saw The Hunger for the first time. Overall, I was a bit disappointed. I found the first act mesmerizing (and soon afterward ran out to get whatever that song about Bela Lugosi being dead was), but once Bowie fully withers and gets put in a coffin, a lot of the narrative spark seemed to leave and never come back.

I haven’t seen it since then — I have no idea if my current evaluation would match my earlier one.

Note: I have now re-watched it, and more or less agree with my earlier evaluation, although it didn’t seem nearly as long to me now.

I watched Cat People because it had a Bowie song as its theme, and The Man Who Fell to Earth because of Bowie, and Labyrinth, and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.

I watched other movies for Bowie cameos, like Zoolander or Basquiat or The Prestige or Fire Walk with Me. He livened up every scene he was in. He had an amazing screen presence to go with his amazing stage presence.

It seems fitting that, in the long run, his most iconic movie role was probably the one in Labyrinth. You know the one. He plays the crazy-mulleted, sparkle-codpieced, ambiguously threatening Goblin King of Sarah’s sexual awakening, in a movie where, ultimately, she rejects him — not because he isn’t incredibly tempting and seductive, but because she rejects any sexuality that isn’t on her own terms.

His offer: Just fear me, love me, do as I say, and I will be your slave!

Her response: My will is as strong as yours, and my kingdom as great — You have no power over me.

Waiting for the gift of sound and vision

My husband Paul and I met at the WWU SF club in the late 1980s, when I was the president. At the time, it was generally assumed that everyone in the club was a huge Bowie fan. It was just one of those things.

The first really significant conversation Paul and I had was mostly about vampires. But it was also about David Bowie. We both agreed that The Hunger was deeply flawed as a movie, but David Bowie was cool.

We had many similar conversations, but it was two years before we would actually start dating. We were at that part of the romantic comedy, where the audience is going, “what the hell is wrong with you guys you’re obviously meant to be together,” and one half of the couple is still going, “nah, he’s too strange and annoying, we’re just friends.”

I lived in Seattle and Paul lived in Bellingham. During this period, all the Bowie albums and CDs seemed to be disappearing from record stores. I assumed it was because he wasn’t hip enough anymore, that he was fading away, and I was losing touch. (Somehow, the idea that I was getting old and losing relevance seemed more important at 21 than it does, you know, now.)

I panicked. I envisioned a day when I could never fill in the holes in my Bowie collection. So, for a while, I combed every Seattle music store for Bowie albums. Mostly, these were vinyl. Some of them ended up being a bit odd — 12 inch singles from poorly recorded live shows, or off-brand singles collections.

Then one day I went to Bellingham to visit the social group I still thought of as the SF club, and caught Paul coming back from Cellophane Square with a newly purchased Bowie CD boxed set that had just been released.

Apparently his stuff had been disappearing because the rights to his back catalog had changed hands. But now the new owners, Rykodisk, were releasing his entire back catalog, and kicking that off with a boxed set, Sound + Vision.

I went downtown immediately to buy my own copy.

A few months later, we started dating. One of our first official activities as a couple was a Bowie concert, his Sound + Vision tour. We got there late and slightly mad at each other, but when we entered the stadium, Bowie was singing “Life on Mars,” and all was instantly forgiven.

When I looked in her eyes they were blue but nobody home

In October of 1995, David Bowie appeared in the Tacoma Dome, touring the album Outside, with Nine Inch Nails as his opening band.

NIN was fantastic. When their set ended, there was a break, during which some hipster kids in front of us made a big show of leaving before that dinosaur rocker guy (Bowie) got on stage, because they were obviously too cool for that sort of thing.

We laughed at them, probably out loud. We had all been young enough, once, to put on shows like that, a studied pose of being “too cool” for something. We knew from experience that it didn’t pay off.

The next part of the set, after the hipster kids were gone, featured Bowie and Trent Reznor performing together on each other’s songs, including “Scary Monsters” (an often overlooked favorite of mine) plus “I’m Afraid of Americans” and “Terrible Lie.” It was pure magic. One of the best things I’ve ever seen in concert. Their combined performance energy was so powerful that it seemed to shrink the distance between the stage and our seats to nothing, even in the vastness of the Tacoma Dome. Magic.

I felt sorry for the hipster kids. They really missed out, more than usual.

I wonder if any of them remember that moment today. I wonder if any of them regret it.

The next day and the next and another day

The last time we saw Bowie in concert, it was 2004 and he was touring with the Polyphonic Spree, in support of Reality, an album that I keep forgetting about.

His performance was great, but there was a moment where he knelt down on the stage — we assumed he was just being dramatic — but then he apologized, calling it “a performance malfunction.” He stood on one foot. The last words we ever heard him say were “I’m not feeling well.”

We started to worry about him a bit. He seemed to drop out of public life.

Then, almost ten years later, we started to see the videos for The Next Day. We were a bit reassured. Oh, he was working on an album. A good album. Maybe he would tour it? Maybe? Pretty please?

No.

Actually.

It turned out that his performance malfunction was probably the result of more serious health problems. Later on in that tour he required angioplasty — something we totally missed at the time.

But, when he came out with another highly regarded album just a couple of years after The Next Day, we were optimistic again. Maybe he wasn’t well enough to tour anymore, but surely he would keep turning out good albums, an almost unheard-of accomplishment for a musician with such a long career. He remained relevant He remained Bowie.

Everybody knows me now

On David Bowie’s birthday, Black Star was released and the music world kinda went nuts. There were birthday/album release parties everywhere. Everyone agreed it was a great album. Everyone agreed that Bowie still had it, whatever it is.

And then, just days later, he was gone.

We looked around at each other, stunned. How was this possible? Wasn’t David Bowie some kind of otherworldly immortal super-being? He always seemed like one. Like a starman who fell to earth, a goblin king, a leper messiah, a queen bitch vampire diamond dog flashing teeth of brass. How could he be an ordinary human, dying of cancer?

But it turned out the only thing otherwordly was his talent. And the only thing immortal was his art.

I wrote this very soon after losing him, and sat on it now for four years. Why? I don’t know. Did I think I had more I needed to say? Did I think, if I never published this eulogy, that somehow he wouldn’t be gone?

Wait, I think it’s that one. The second one.

Farewell.